“Who gathers the most

dust?” he asked her, grinning.

“Heidegger? John Stuart

Mill? Derrida?”

“It’s pretty evenly

distributed,” she told him.

“That’s too bad,”

said Michael, taking another sip of tea, “I was sort of hoping old Heidegger

would be the front-runner, dust-wise!”

“Dust-wise?”

“A rolling

philosopher gathers no dust,” he assured her.

“What on earth do you

mean?” May asked him.

“Oh nothing, really.

I’m just talking silly to justify my sitting here and gazing at you.”

May put down the

feather duster and gave him a kiss on the forehead.

“Don’t you have anything

more pressing to do?”

“I do, but I’m

putting it off for as long as possible.

I sort of half-promised a painter I know that I’d go see his work. A guy named Homer Rubik.”

“That’s an odd name,”

said May, moving from the philosophy section to the history section.

“Well, he’s an odd guy,” said Michael, “and his name suits him

nicely. ‘Homer’ may be a bit lofty

for him, but “Rubik’ is perfect—like the infamous cube, he’s shifty, lots of

sides, lots of angles, ultimately unknowable, and, in the end, probably

pointless.”

“Why do you care

about him then?”

“I don’t,

really. But the stuff he makes is

extraordinary—in a sort of unhealthy, unwholesome way.”

“What’s it like?”

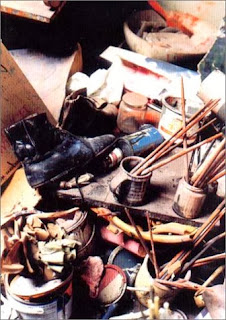

“Very strange. It’s like Old Master painting, but small—on

scrap pieces of paper. He paints

on anything—envelopes, butcher paper, newspapers, pages torn from magazines,

flattened-out cardboard boxes….

He’s like a back-alley Raphael or Caravaggio!”

“So you’re going to

visit his studio?”

“Well, he doesn’t

really have a studio.

The guy is a short-order cook in a diner.

I’m told he lives in a two room apartment and apparently paints in his

kitchen.”

“Maybe he’s a

genius!”

“Yeh maybe.”

“But probably not?”

“No, probably not.”

“And now you’ll see for yourself.”

“Yeh. Lucky me.

It took Michael some time, but he finally found

what he took to be Homer’s little flat—high atop the rusty fire-escape at the

back of a five-story building on Stafford Street, south of Trinity Bellwoods

Park. He was standing at the foot

of the stairs when he suddenly spied Bliss Carmen, leaning over the railing outside

Homer’s door. Fish was with her,

of course, and took this opportunity to undertake a feat of aerial bladder

evacuation, cocking his left back leg against one of the steel railings of the

fire escape and pissing a yellow rain that fell perilously close to Michael.

“Missed you!!” cried Bliss happily.

“Yeh,” said

Michael. “The happy intervention

of a sudden breeze from the west.”

“C’mon up!” boomed Bliss.

Michael climbed the

fire escape, feeling more certain with every step that this whole visit was a

mistake.

Bliss led him into

the first of Homer’s dank rooms. It seemed to be some kind of sitting room, though

there really wasn’t anyplace to sit.

There was a greasy mattress on the floor.

“That’s where we

sleep,” Bliss announced. “This is

our boudoir.”

Michael suppressed a

shudder. A shudder not so much

engendered by the ad hoc bed as by the whole idea of sleeping with Bliss. Geez, thought Michael to himself, did any woman ever bear such an inappropriate

name!

He heard Homer

stirring in the second room.

“Homer,” boomed

Bliss, “get out here!

My big Writer Friend is here!”

“You mean Zorba?”

muttered Homer.

Michael felt like

strangling them both.

“Yeh, he might write

something about your work!”

“Listen, I never said

I…” Michael began when Bliss shushed him.

“Don’t be like that,”

she told him in a loud whisper. “Homer needs encouragement.”

Homer finally appeared

in the doorway, naked to the waste, his jeans stiff with what Michael supposed

might equally be dried oil paint or congealed egg.

“You come to see my

stuff?”

“Yes,” Michael, told

him. “You have some things here?”

“I’ve been doing

stuff,” said Homer.

“Home’s very

prolific!” boomed Bliss. “He always has work around!”

“Okay,” said

Michael. “Let’s look through some

things.”

Home returned to the

second room—the kitchen he used to paint in—and beckoned Michael to follow.

“I would have thought

you’d have had enough

of kitchens!” said Michael, trying for a preliminary pleasantry.

“What?” said Homer.

“Michael means that

you just seem to go from one kitchen to another!”

she said heartily. “That’s what

you meant, wasn’t it, Michael?”

Michael smiled

weakly.

“Fish, stop that!!” yelled Bliss suddenly. Fish had lifted his leg and peed

copiously on a pile of ink drawings.

The ink had now begun to run and was pooling on the floor.

“Ha!” laughed Bliss,

“a new medium!”

Homer gave Fish a

kick.

“Andy Warhol did a

series of piss paintings once,” said Michael. “They were on metal.

He called them his ‘Oxidation paintings’ because the urine changed into

beautiful colours when it dried on the metal backing!”

“Who?” asked Homer.

“Andy Warhol,” said Bliss, speaking loudly and

distinctly to him as if she were speaking to someone with hearing problems.

“So what?” said

Homer.

Michael couldn’t

think of a good answer.

“